InnoFuels beim Fachkongress „Kraftstoffe der Zukunft 2026“

Der 23. Internationale Fachkongress „Kraftstoffe der Zukunft 2026“ ist am 20. Januar in Berlin erfolgreich zu Ende gegangen. Über 620 Teilnehmende aus Politik, Wirtschaft, Wissenschaft und Verbänden diskutierten an zwei intensiven Konferenztagen die Rolle erneuerbarer Kraftstoffe für eine klimaneutrale Mobilität und die notwendigen politischen sowie regulatorischen Weichenstellungen für den Markthochlauf.

Der Kongress bestätigte eindrucksvoll: Die Technologien für erneuerbare und klimaneutrale Kraftstoffe sind verfügbar und praxiserprobt – entscheidend sind nun verlässliche, langfristige Rahmenbedingungen.

Starke Präsenz des InnoFuels-Teams

InnoFuels war auf dem Kongress mit mehreren hochkarätigen Beiträgen vertreten und brachte seine wissenschaftliche und systemische Expertise gezielt in den Dialog zwischen Forschung, Industrie und Politik ein:

Zum Beispiel mit dem Fachvortrag mit dem Titel "Der reFuels-Ansatz von der Forschung zur industriellen Praxis" von Prof. Nicolaus Dahmen und Dr. Olaf Toedter (beide KIT). Der Beitrag stellte zentrale Ergebnisse und Zusammenhänge der thematisch eng verzahnten Projekte InnoFuels, REF4FU und reFuels vor. Im Fokus standen:

- reFuels als akademisch-industrielles Kooperationsprojekt,

- der Weg von reFuels von der Forschung zur Demonstrationsanlage,

- sowie der aktuelle Stand der Umsetzung.

Der Vortrag zeigte eindrucksvoll, wie das enge Zusammenspiel von Forschung und Industrie dazu beiträgt, innovative Kraftstofflösungen gezielt in die Anwendung zu bringen.

Darüber hinaus setzte Dr. Franziska Müller-Langer (DBFZ) mit ihrem Impulsvortrag „Factor 10 by 2050 – Renewable fuels between aspiration and reality“ wichtige inhaltliche Akzente. Sie beleuchtete die Spannungsfelder zwischen langfristigen Klimazielen, technologischen Möglichkeiten und realen Rahmenbedingungen. Zudem moderierte sie die Session „The long road to e-fuels: success and challenges“ und förderte damit einen offenen fachlichen Austausch zu Chancen und Herausforderungen synthetischer Kraftstoffe. Weitere Beiträge aus dem InnoFuels-Team kamen von Torsten Schwab (International PtX Hub) und Michaela Unteutsch (Frontier Economics).

Table of contents

sprungmarken_marker_962

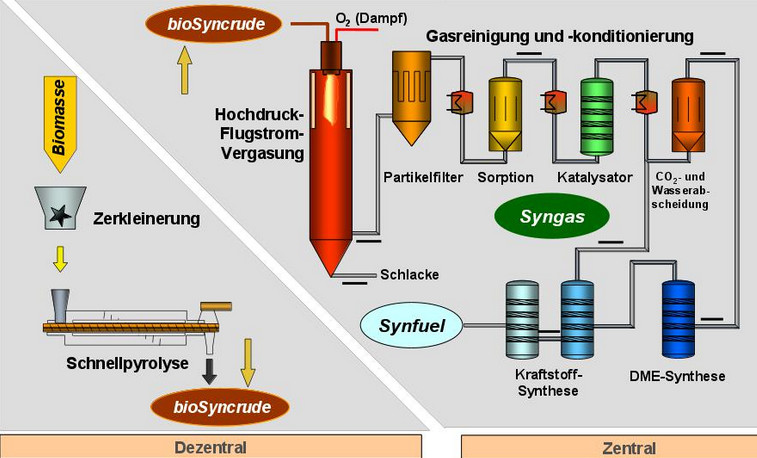

20 years of bioliq® – From straw to innovation

Twenty years ago, one of the most ambitious projects for the production of synthetic fuels from residual biomass was launched: bioliq® has set standards, mastered challenges and achieved important milestones. In this interview, project manager Prof. Nicolaus Dahmen looks back on the history and current relevance of the project.

On April 2, 2025, the symposium "Methanol-based fuels" took place at DECHEMA House in Frankfurt am Main, organized by the "Production" team of the InnoFuels innovation platform. Experts from science and industry came together to discuss the current status of methanol-based fuels and the associated challenges. Incidentally, the idea for this came about almost two years ago during the BMDV Renewable Fuels Conference, when the funding decisions for the twelve projects in the funding line of the same name were presented. As several projects are working intensively on methanol-based fuel paths and their possible applications, an in-depth exchange was the obvious choice. InnoFuels has now taken up this impulse with the symposium.

In addition to specialist presentations on the ongoing projects, the subsequent workshop discussed specific approaches on how the development of methanol-based fuels can be accelerated and driven forward. Key topics included the provision of renewable methanol and the processing of methanol into fuels, new business models for a successful market launch and research questions on further technological development.

The sharing of expertise and cooperation in the working groups proved to be extremely enriching for all participants. It has become clear that the success of methanol-based fuels can be driven decisively by more intensive cooperation between research institutions, industry and start-ups. The event has thus provided an important impetus for further networking between the players and the development of innovative solutions. InnoFuels will continue to actively promote this cooperation and intensify the exchange between the participants in the future.

%20KIT_Markus%20Breig%20und%20Amadeus%20Bramsie-3.jpg)