Table of contents

sprungmarken_marker_967

Symposium: Biofuels & Additives for the shipping industrie

The shipping industry is facing a profound change: climate targets, stricter emission regulations and increasing demands for sustainable logistics solutions require new approaches for environmentally friendly drives. Liquid drop-in biofuels and innovative additives are becoming increasingly important in this context, as they can be integrated into existing systems without major conversions and also offer the potential to effectively reduce emissions in the short term.

At the same time, many questions remain unanswered - from fuel quality and engine compatibility to costs and availability, regulatory requirements and practical experience from real-life applications. InnoFuels is hosting a symposium in Rostock on April 21, 2026 to shed light on these aspects. The event is being organized by the LKV Rostock and the Research Center for Internal Combustion Engines and Thermodynamics Rostock (FVTR).

The event brings together authorities, fuel producers, engine and component manufacturers and users from the shipping industry. The aim is a focused exchange on current market developments, technological advances and concrete experiences with alternative fuels.

Everllence, Infineum, Finco and Hapag-Lloyd, among others, will provide insights into their previous findings, current projects and plans for the future. This will provide a compact, practical picture of the role that alternative maritime fuels can play on the way to more sustainable shipping.

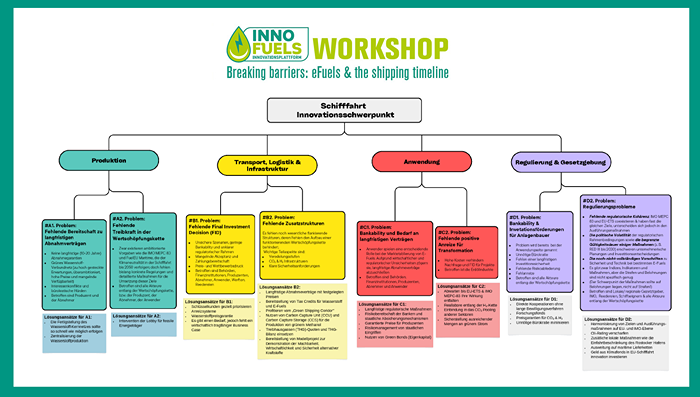

Workshop: Breaking Barriers - eFuels & the Shipping Timeline

On June 12, 2025, key players from the maritime value chain came together in Rostock to identify obstacles to the introduction of climate-neutral marine fuels. With a focus on the Rostock model region, practical measures were developed for a rapid market ramp-up and a sustainable maritime energy transition.

All results and recommendations for action are documented in this PDF.

At the large engine conference in Rostock on September 12 and 13, Dr.-Ing. Karten Schleef will shed light on the current challenges in shipping and explain how the use of renewable fuels could advance the industry. The Rostock Large Engine Conference, which is co-organized by the Chair of Reciprocating Engines and Internal Combustion Engines at the University of Rostock, serves as an international forum for the exchange of ideas between legislators, researchers, developers and operators of large engines. This year, the InnoFuels project will also be present with its own stand.

Why does it make sense to present the InnoFuels platform project in Rostock?

The RGMT clearly reflects the change in topics in the world of large engines over the last 15 years. While the focus until around 2010 was still primarily on ever higher efficiency and reliability, the focus then shifted to compliance with nitrogen oxide legislation or sulphur specifications. For around 5 years now, the industry has been working intensively on the introduction of alternative marine fuels such as methanol and ammonia. This will also involve making the required climate-neutral fuels available on a large scale. What regulation is necessary? Who will produce the fuels? How do tank farms need to be converted and what bunker infrastructure needs to be available in the ports? These are just some of the key questions that the InnoFuels network is working on. So these are exciting times.

What is the current proportion of renewable fuels in international shipping and what specific types of fuel are used?

So-called Sustainable Marine Fuels (SMF) have unfortunately hardly been bunkered to date. According to the International Maritime Organization (IMO), they currently only account for around 0.1 percent of the fuel volumes documented worldwide. The SMFs available today are almost exclusively of biogenic origin. Electricity-based fuels such as methanol or ammonia are only at the beginning of their development. There are currently around 40 to 50 ships that can be powered by methanol and only the first test engines for ammonia.

So there is still a lot of room for improvement. Nevertheless, shipping is considered the most climate-friendly mode of transport. How does that work?

Around 90 percent of the world's goods are transported by sea. As ships have a significantly higher transport capacity than trains, planes or trucks, the greenhouse gas emissions per tonne and kilometer are unbeatably low. Nevertheless, the industry can contribute to further reducing the need for precious eFuels for defossilization and climate-neutral operation of the shipping fleet through additional efficiency improvements such as weather-based route optimization, bubble carpets, propeller retrofits and similar measures. Ultimately, this is only possible for seagoing vessels by using alternative and sustainable fuels with a high energy density.

Emissions of air pollutants such as NOx, SOx and particulates are an issue that is currently being pushed into the background. After all, the proportion of air pollution caused by ships in port cities and coastal regions can already exceed 80 percent. The industry must therefore proactively do more to reduce exhaust emissions. With the new sulphur-free fuels, many exhaust gas aftertreatment technologies known from road traffic are now also possible for shipping.

In the InnoFuels application field of shipping, which you are in charge of as an expert, the main focus in recent weeks and months has been on investigating the obstacles to the market launch of renewable fuels. What insights have you gained?

In general, the transformation of the fuel market in shipping is still in its infancy. The market has so far been dominated by short-term contracts without long-term commitments between suppliers and customers. However, such long-term commitments are necessary so that both sides have planning security. Without this security, important investments in fuel production facilities, bunker infrastructure or new ships will be delayed. There is also a risk of competition for use with the chemical industry and aviation, as the shipping industry uses intermediate products or chemical base materials as fuels.

As the industry is very heterogeneous, the individual shipping companies are differently prepared for the impending change. In addition, there is a growing bureaucratic burden to prove compliance with new laws such as FuelEU Maritime and the integration of shipping into European emissions trading. A key question is whether the incentive systems are sufficient to close the price gap between standard fossil fuels and climate-friendly alternatives. How can competitive disadvantages for first movers be reduced? As the International Maritime Organization (IMO) will not adopt a legally binding roadmap for reducing the greenhouse gas intensity of the fuels used on board until 2027 at the earliest, the industry is still adopting a wait-and-see approach.

On the other hand, important impetus is coming from freight owners who want their goods to be transported in a climate-neutral manner as "premium green" in order to offer their customers added value. Although these initiatives have only been on a small scale so far, they could provide an important incentive for fuel production. In addition, banks are offering modified financing models for green ships, allowing easier access to funding or improved conditions. Networking the many different players is therefore particularly important.

What are the next steps in the InnoFuels focus application field of shipping?

We have just commissioned a study to analyze the challenges faced by shipyards in the course of transforming the shipping industry into a green industry. We expect this study to provide important impetus for clarifying the question of which core technologies need to be developed in shipbuilding in order to make the fleet climate-neutral by 2050.

Next, we are planning a workshop to examine the complex interplay between the supply chain, production and application in the future eFuels markets of shipping and distribution transport in the hinterland using Rostock as a model location. This is because we will see a concentration of imports and the conversion of energy sources in the vicinity of the North German seaports: for example, the landing of renewable offshore surplus electricity, methanol or ammonia imports, the installation of large crackers or CCUS plants. How can these technologies be clustered efficiently and sensibly? How can significant off-take volumes that are important for final investment decisions be ensured? Regular ship calls, such as ferry lines and hinterland transportation in the logistics sector, play an important role here.

In addition to the University of Rostock, the engine manufacturer Rolls-Royce is also involved in the InnoFuels project. Is it possible to get other companies on board?

In general, the entire large engine industry and everyone who comes into contact with fuels in the shipping industry is invited to actively participate in InnoFuels. This could be through participation in workshops in the further course of the project, for example. We will also conduct surveys and expert interviews on the more technical or regulatory hurdles currently facing the industry. In order to serve as a point of contact and to be able to address central demands, we have therefore also decided to participate with the InnoFuels project as an exhibitor at the RGMT trade fair accompanying the conference.

%20KIT_Markus%20Breig%20und%20Amadeus%20Bramsie-3.jpg)